Open Goldberg Variations, mission accomplished

by Alexandre ProkoudineThe Open Goldberg Variations project has reached the last milestone: recordings and scores are available as public domain for admirers of classical music.

The Open Goldberg Variations project has reached the last milestone: recordings and scores are available as public domain for admirers of classical music.

Goldeberg variations by Johann Sebastian Bach were originally composed for harpsichord. The score was published in 1741 while Bach was still alive, which was rather unusual in his case.

A collaboration between developers of MuseScore, a professional pianist Kimiko Ishizaka, her husband Robert Douglass who organized the project, and the producer Anne-Marie Sylvestre, Open Goldberg Variations made quite a splash last year, being one of the first successful Kickstarter campaigns in the classical music field.

The reason? The Kickstarter page is quite emphatic about that: “It’s a shame that a work which has been in the public domain for hundreds of years is still hard to acquire and enjoy in both its notational and its recorded form. By making a public domain score and recording we’re solving that problem.”

Kimiko Ishizaka, the pianist, adds: “It is frustrating that good versions of the public domain works aren’t available online. Prior to the Open Goldberg Variations, the range of scores for this piece that could be downloaded for free was really small. So in that way we’re really making a great contribution.”

She continues: “I’m hoping that there will be people who learn to love Bach, and the Goldberg Variations, because they find my work online for free, and give it a chance. They might always walk by the CD rack in the store without bothering to discover the beauty of this music, but now we’ve lowered the cost of trying it out to nothing. It would really make me feel successful to find out someday that someone loves the Goldbergs because of this project.”

Would you believe that such an ambitious and clearly cultural project could be born in the geeks department? And yet it was.

How the Open Goldberg Variations project started

It came from our internal MuseScore brainstorms” — Thomas Bonte, MuseScore developer, recalls — “We saw the Musopen kickstarter project and we were basically looking to do the same, but adding the open source score to it. As Robert is a long time friend of mine, we shared the idea. And as his wife is a professional piano player, it was a match.”

The team soon realized they’d rather focus on the score engraving and software development part and passed the torch to Robert, a formerly classically trained musician himself, who quickly set up the project’s website and started promotion activity.

A month later the Kickstarter campaign was launched. In June 2011 it ended, and the goal ($15K) was exceeded by over $8K thanks to 406 backers. In January 2012 recording started, and now all of Goldbergs are finally available to everyone, free of charge.

Bringing MuseScore to the state of the art

By the time the kickstarter campaign launched Werner Schweer, principal developer of MuseScore, was already deep in work with score engraving. For this project Werner used four sources: the original Bach script which was very hard to read for him, a Busoni edition, a Czerny edition and a modern Henle edition.

The project turned out to be demanding for MuseScore. Werner says: “During the preparation of an initial version of the score I saw several deficiencies and possible enhancements of MuseScore. This has influenced further development of MuseScore a lot”.

What he discovered was that the MuseScore was missing some features required to create a high quality score. Implementing those features took some time. Here are just a few examples.

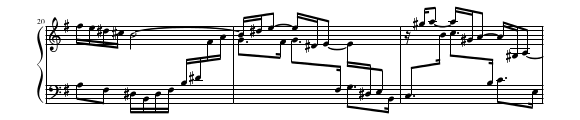

The score is partly very dense and uses several voices and extensive cross staff beaming. Done:

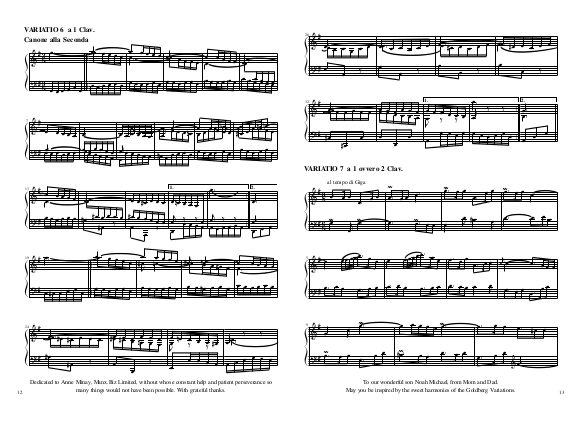

In few cases a staff starts with a violin clef which is immediately followed by a bass clef without any notes between them. As MuseScore associated clefs with time (tick) positions, it was impossible to have more than one clef at one tick position. Done:

The work on these improvements was made in the unstable branch of MuseScore that will eventually become v2.0.

Working on the score and the cultural context

Meanwhile Kimiko Ishizaka started working on the project: “For me, the Open Goldberg Variations project meant the chance to seriously study and focus on one of the most wonderful works of all time. With the support of our fans, and my husband Robert, I had the time and clarity that is needed to look deeply enough into such a complicated work to really know it.

Kimiko was also actively involved with creating the score: “The process of working with Werner Schweer on this score was really fun. There is a lot of work that goes into reviewing the typesetting, and the accuracy of every note. That’s the value that the famous editions of these works bring to people. We also put a lot of work into this score to make it a valuable tool for musicians.”

As the result, the complete BWV988 is publicly available.

New frontiers

Interestingly enough, the collaboration between the musician and the MuseScore developers doesn’t really stop there. Let’s make a detour.

For the MuseScore project the musescore.com website is becoming a hub for pretty much all future developments. Apart from working as a cloud storage of scores which can be downloaded from both MuseScore and various mobile apps it now has some extra features. One of them deserves a special attention: it’s part of the newly developed score following solution.

Simply put, if you are at a concert with a smartphone or a tablet (iOS, Android etc.), and the score exists at musescore.com, you can see the score in the browser, and while the performer is playing, you can see the score move up, measure by measure.

From technical point of view, MuseScore.com API serves the data, and a node.js server distribute the changes such as measure changes. However right now it’s not like you could go to an arbitrary concert with an iPhone and watch the score. After all, the world domination doesn’t happen overnight.

Thomas explains the back story: “First time we started to work on score following was in Feb 2011 in New York with researcher Matt Prokup. We then started to work with a company from my home town Gent, in Belgium, called SampleSumo, which resulted in a follow-up hack, in Barcelona, June 2011. Later, in January 2012, there was another hack day in Cannes, France — yet another follow up on the same hack, but we added an audience component to it.

This new technology will be publicly demonstrated in Munich in just few days at Classical:NEXT. But it’s not the first demo. Kimiko elaborates: “We’re doing some concerts where the MuseScore is used along with SampleSumo to follow the score, and we project it to the audience so they can see what I’m playing. You can put it on a website or Facebook. It’s just a whole new world of possibilities.”

Would it be somewhat disturbing if people started attending classical music concerts armed with iPads and meticulously following scores? Kimiko doesn’t agree that it’s likely to happen: “Music is a spiritual experience. Many people listen with their eyes closed. I think there’s a place for the score following, but it won’t become a standard part of performances. People should be inspired to try new things, and to find creative ways of enjoying the cultural treasures that we have. So we’ll keep experimenting with it and see what comes of it.”

Thomas takes a relaxed view as well: “Professional musicians have told us that indeed it distracts and adds an extra sense, and thus it takes away the ability to hear the finesses, richness, etc. But then again, people who can’t read sheet music feel empowered, because they are able to hear real time what they see. Somehow, they get the ability to read sheet music for the first time in their lives.”

Kimiko concludes: “I think it’s fun to explore the possibilities, but I don’t think that it’s a particularly good idea to have lots of iPads going during the concert. A better application for these technologies is the iPad app itself, that the MuseScore team is working on. That gives you a really intense way to experience the music, with the audio and the score there in your hand at the same time.”

What’s next

As you are reading this, an OpenGoldberg app for iPad is moving forward in the review queue for the AppStore. The app will download the complete OpenGoldberg recording and on playback the MuseScore sheet music will play along. The application uses the very same MuseScore library that drives the internals of upcoming MuseScore 2.0 and various apps for mobile devices.

The team has three parallel tracks now: desktop, web and mobile. For desktop, it’s about getting MuseScore 2.0 released with all the changes introduced for last couple of years.

For web, it’s improving musescore.com, making it more social and improve interaction between MuseScore 2.0 and musescore.com.

As for mobile, it’s releasing the musescore.com app for iOS first, and the Android application after that. The musescore.com app will offer playback, tempo change, font resize, tranposition, parts, etc. Eventually, the score follower will be part of the musescore.com app as well.

But wait, is that all there is to this Kickstarter campaign? No more projects like Open Goldberg Variations? Thomas clearly enjoys having a card up his sleeve: “Let’s put it this way… What if we could open source all public domain scores with MuseScore?”

Patreon subscribers get early access to my posts. If you are feeling generous, you can also make a one-time donation on BuyMeACoffee.