This article explains the difference between embedding and linking in Inkscape and advices when to use each of them.

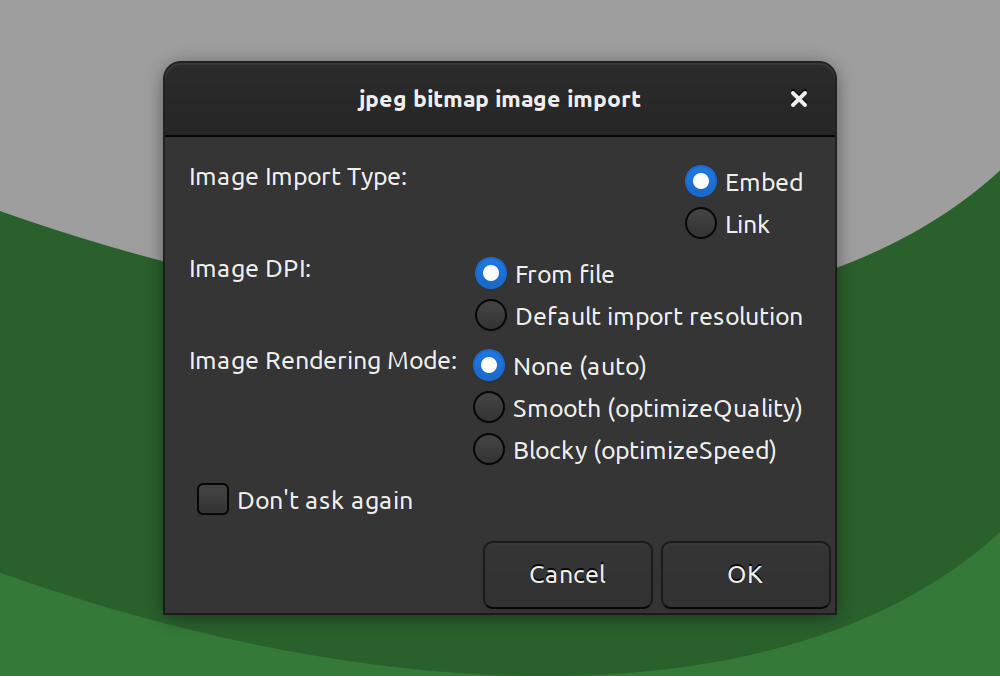

The question popped up again, this time — on inkscapeforum.com. Since 0.48 whenever you drop a bitmap image into an Inkscape’s document (or use File > Import…), you get exactly this dialog:

Never mind the techie lingo is the window’s caption. The dialog actually explains what happens, but it never hurts to elaborate.

Which is which?

Embedding is a bit of technical jargon. It means placing files inside other files. When you choose embedding, a copy of an image file you dropped into Inkscape’s document will be saved inside this document. So if you choose “embed”, Inkscape will later load this image as part of SVG document, just like a Bezier path or circle or text.

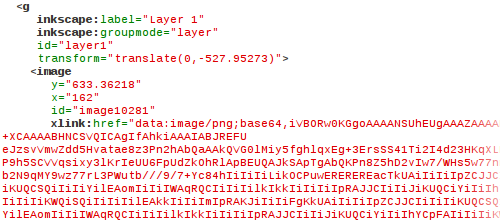

If you are into details, because SVG is essentially a text based file format, that image will be encoded with base64 — a kind of textual representation of non-textual data. Here is what the relevant bit of the SVG file will look like:

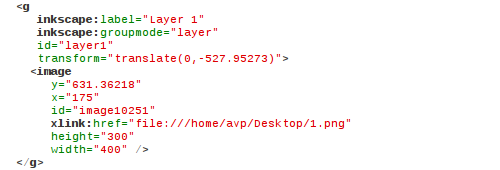

Linking means that Inkscape saves information about location of this image inside SVG document. So every time you open a document that links to an image file, Inkscape will try to find this image in the location that was saved inside SVG document, load it and show it to you. Again, here is the relevant bit from the SVG document:

If you want more technical details on linking, you can read the related part of SVG specification.

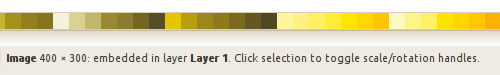

How to tell the difference between an embedded image and an linked image if they just load and look OK? If you never paid much attention to the status bar, it’s about time you started doing so.

When you select an embedded image, the status bar message says exactly that:

However, when the image is linked, the status bar shows full path to an image and its name instead:

So, embedding or linking?

In terms of default Inkscape’s behavior, it’s all down to workflows really.

If you only use Inkscape to provide non-SVG data to your client (sliced design of a website, PDF with a postcard, et cetera) and you never move files around, you can freely use linking.

If you are used to sharing your project files via Dropbox or SparkleShare, or just carrying stuff between desktop and laptop, you probably want embedding.

Why does it matter? One important thing to understand here is that Inkscape always saves absolute paths by default when you choose linking. This means that full path to an image will be saved, from top system folder down to the folder where you actually keep the image.

(This is also the reason why in case of previously unsaved SVG documents Inkscape puts copypasted images, as well as bitmap copies of vectors to user’s home folder — so that they are locatable.)

So if you copy your SVG file to a different computer, you will also have to (at least partly) replicate the folders hierarchy, otherwise Inkscape won’t be able to locate your image automatically. Alternatively you will have to manually edit path to the image and then do it once again every time you copy your SVG to a different system. Needless to say, this can be quite exhausting.

Embedding also prevents images from being accidentally changed by a different application, while with linking Inkscape will honestly open whatever is referenced in the SVG document, even if the image was inadvertently changed. On the other hand, being able to change images from outside can be desirable, especially if the image in question is an exported flattened composition of a multilayered GIMP project that you keep changing.

Sounds like it’d be nice to be able to un-embed an image or embed a previously linked image. It is possible? Yes.

Swapping embedding and linking

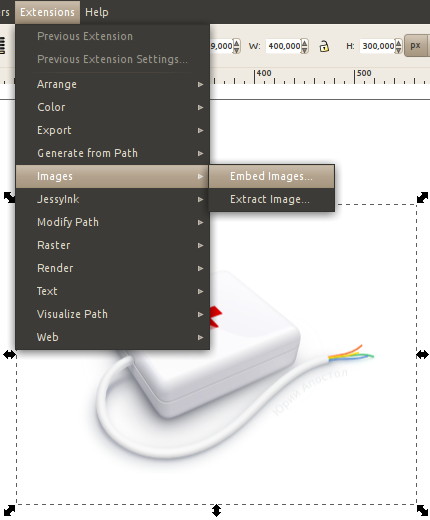

In the current version of Inkscape, 0.48, you can embed and/or extract selected images via these two commands from Extensions > Images menu:

If you choose embedding, Inkscape will show another dialog to ask if you want embedding just currently selected linked images or all linked images.

If you choose extracting, Inkscape will ask you where to store your images. If extraction was successful, embedded images will automagically become linked.

There’s one more important matter to discuss.

Relinking

Up till now we discussed default Inkscape’s behaviour — things you see without getting your hands really dirty. Now roll up your sleeves: it’s time to learn about relinking.

Relinking means telling Inkscape to use an image from a different folder or, if you wish, even a different image.

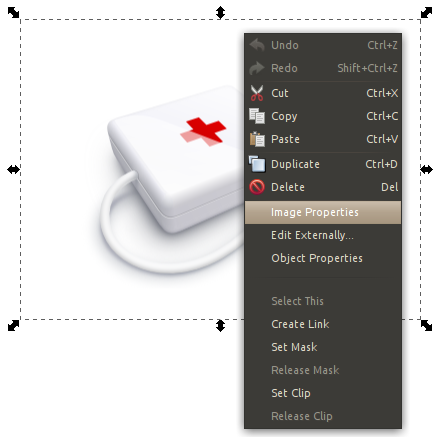

Let’s say you added an image to your document by linking to it. Right-click on the image and choose Image Properties menu item:

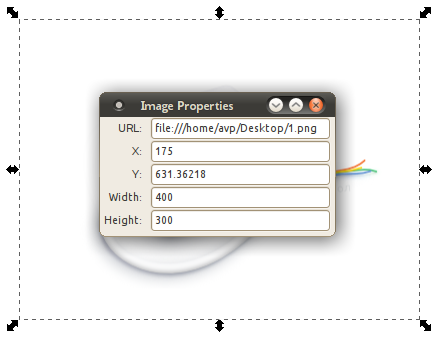

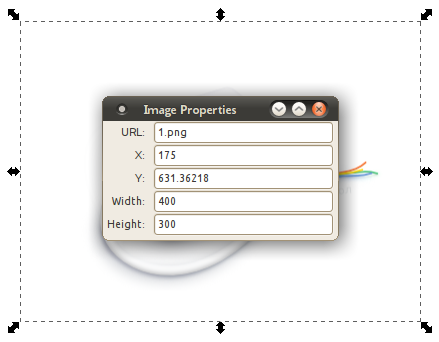

What you get is a dialog that apart from everything else shows current path to an image:

If you want just simple relative paths, when bitmap images are in the same folder as SVG, simply remove current path and leave only name of file, in this case — 1.png:

Once again, in that case Inkscape will always look for 1.png in the same folder where the SVG file is. Thus the SVG document becomes safely shareable.

You can also use “../1.png”, if the file is in an upper folder, or “bitmaps/1.png”, if the file is in “bitmaps” folder that is inside current SVG document’s folder (i.e. nested folder). Of course, in this case should you want to share your project, you’d also have to share upper folder or nested folder respectively.

Bottom line

Embedding is safest way to share your SVG file or move it from computer to computer at the cost of file size.

Default linking with absolute paths is fine as long as you keep your work on one computer and never move folders.

Custom relative links help sharing project data or moving it around at cost of having to manually change paths and allowing images to be inadvertently changed.

Is there a better way to handle images?

Surely someone would think of making this easier for users? Indeed, it’s exactly what happened. Last year a group of students from Centrale Lyon led by Steren Giannini worked on improving the existing tools for embedding, linking and relinking. You can read more about the project here. With luck improvements will be part of v0.49 thus obsoleting half of this article, so it’s a call for patience. Which, purely coincidentally, is a virtue,

Courtesy first-aid kit image by: Yuriy Apostol

Patreon subscribers get early access to my posts. If you are feeling generous, you can also make a one-time donation on BuyMeACoffee.